We would like to reflect on how graffiti-related penalties in the United Kingdom became extremely severe back in the 2000s—much harsher than in many other European countries. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, British authorities, especially the British Transport Police, pursued graffiti writers aggressively. Many were arrested, given long sentences, and even faced prison terms for ordinary graffiti on trains and public property; one example was a young writer sentenced to 28 months for spray-painting trains. Another writer received a long prison term and later took his own life in prison.

A key reason for the harsh approach was that British law sometimes treated coordinated graffiti not simply as vandalism but as a “conspiracy”—a concept typically used against organized crime. This meant that even discussing or documenting graffiti could be viewed as criminal.

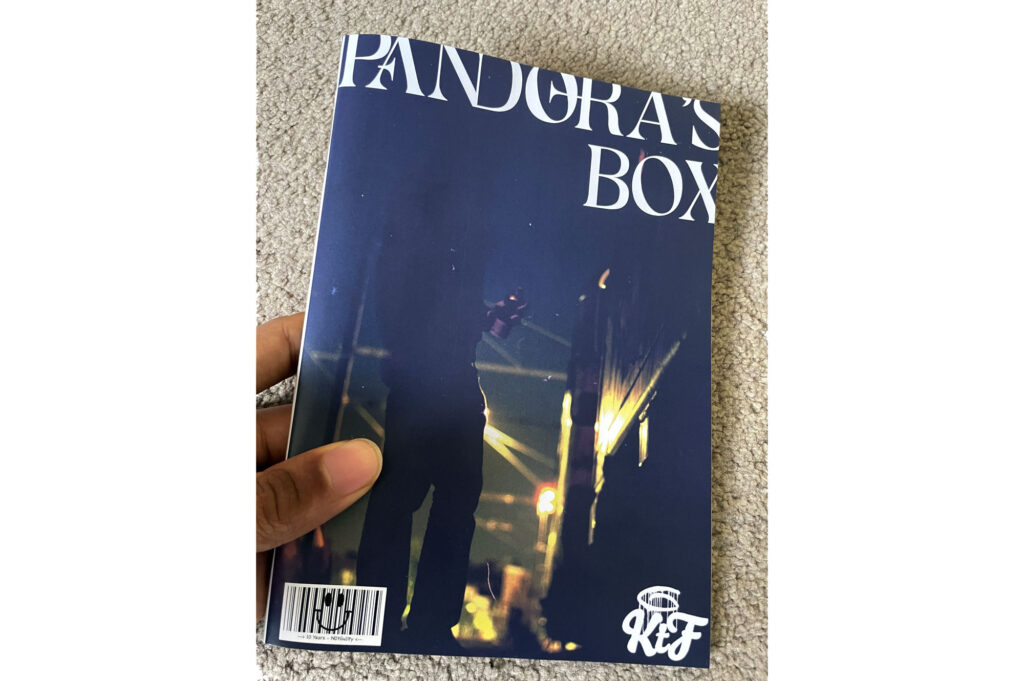

And here comes the story of Marcus Barnes, a London graffiti writer alias @puno.one, enthusiast and journalist who published a zine called Keep The Faith. Because his publication featured illegal graffiti and the people behind it, the police tried to prosecute him for “encouraging criminal damage.” This was an unprecedented legal strategy aimed at making him responsible for inspiring others to paint illegally. Barnes spent more than three years on bail and went through a high-profile trial, but eventually a jury found him not guilty—a historic outcome that could protect others who document graffiti from similar charges. He has since published a new zine, Pandora’s Box, that revisits his early years in graffiti culture and the experience surrounding the trial. The piece situates this legal saga within a broader context of British exceptionalism in graffiti law enforcement, where graffiti was treated more severely than in many other countries, and even journalism about graffiti nearly resulted in criminal conviction.

Marcus has provided us with a personal and very insightful essay to accompany this release, which we would like to share with you here.

Thought Crime? The Trial of an English Graffiti Magazine

An article by Marcus Barnes

When I got arrested and charged with “Encouraging the Commission of Criminal Damage” through my magazine – Keep The Faith – and its blog, I had no idea what a historic moment that would be.

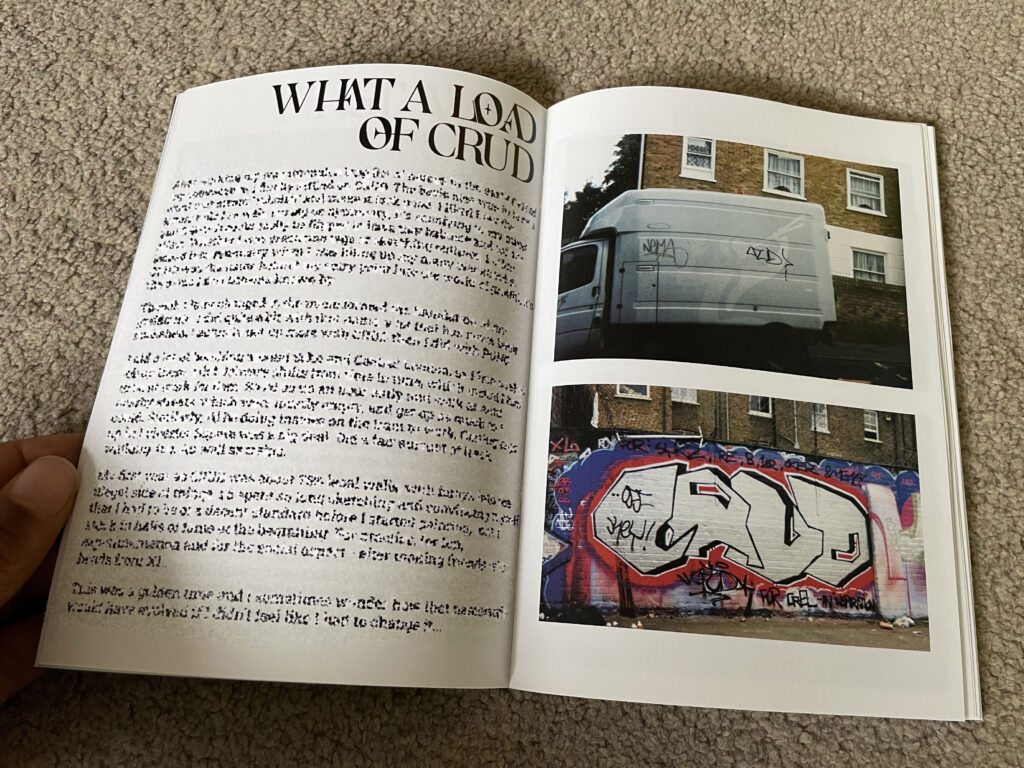

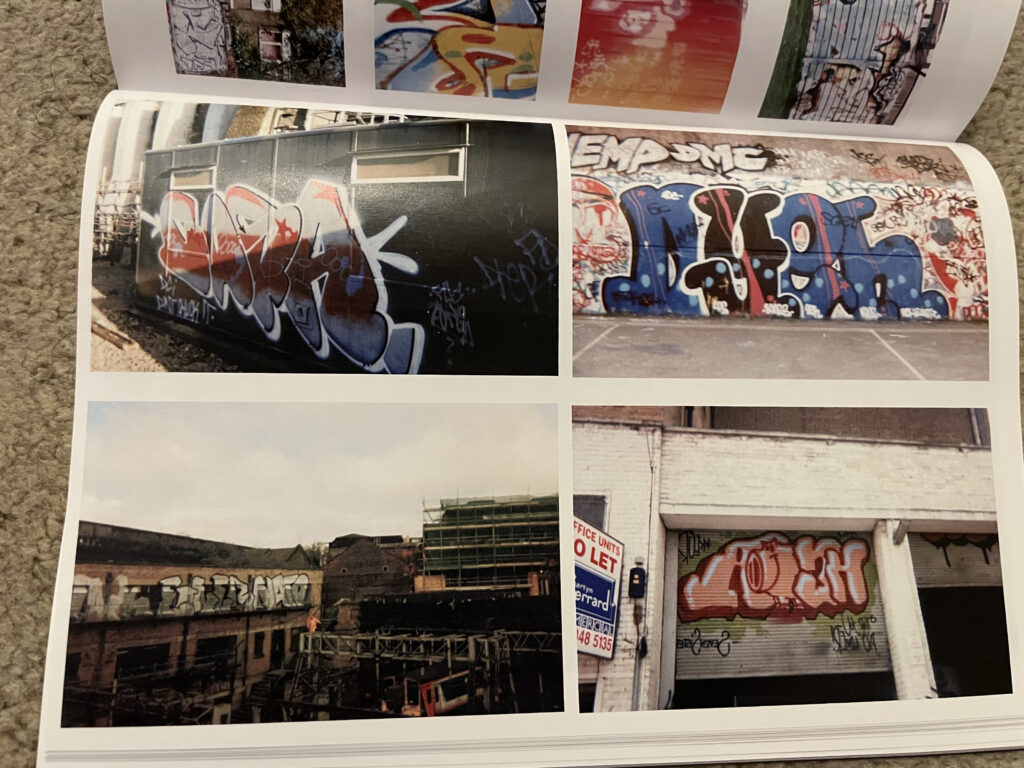

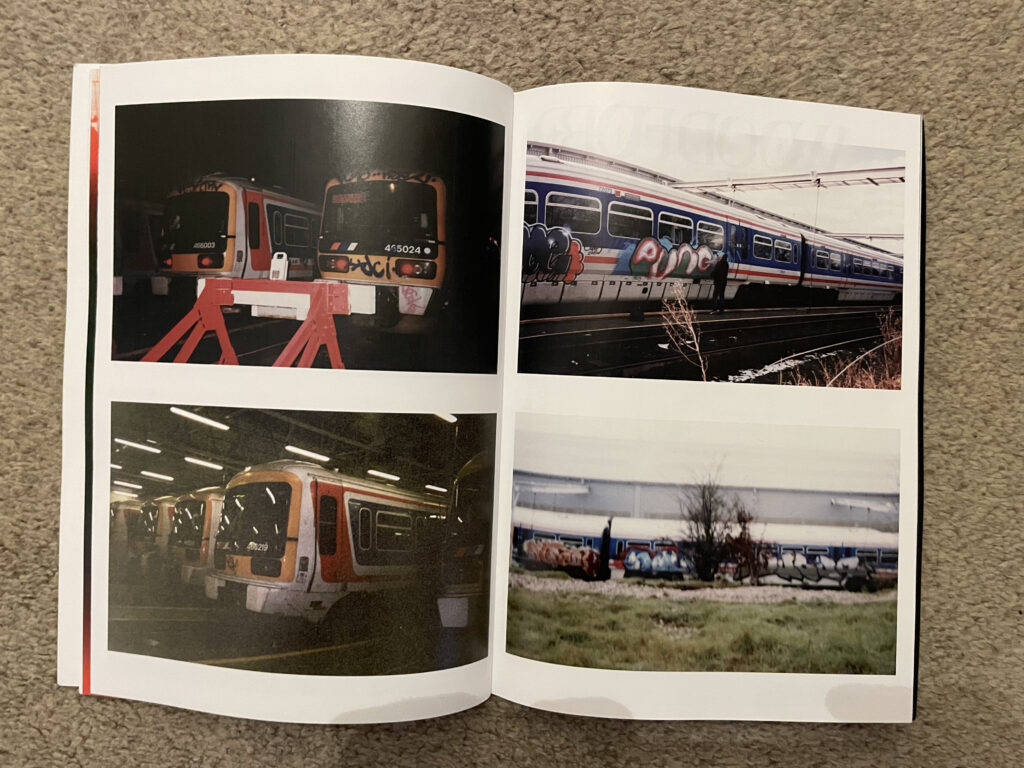

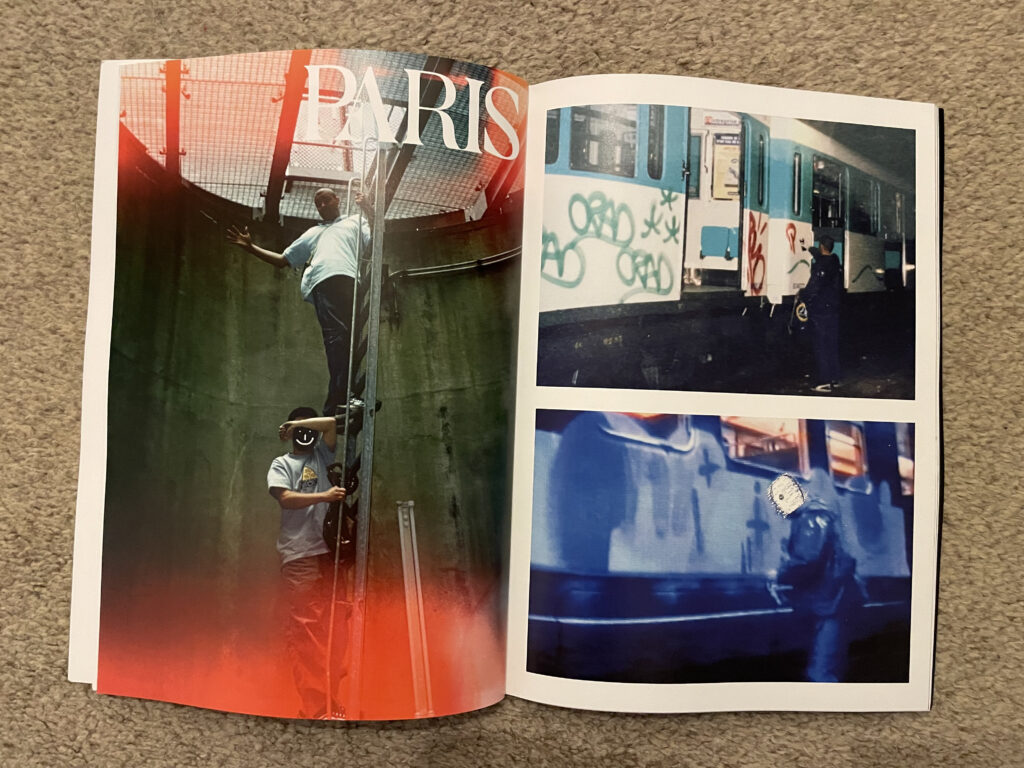

I’d had a feeling that the magazines might bring unwanted attention from the police. In fact, a good friend warned me to be careful not long after the first one came out in 2009. The mags were packed full of illegal graffiti, mostly on trains in London and the rest of the UK – plus some overseas action. Hardcore, yes, but no different, I thought, to any of the other hundreds of mags, books, DVDs and websites that were already out there. If they were going to come for me, I thought it would be because I had some of the city’s most wanted writers in the magazine, and that the British Transport Police would press me for their details.

Thinking about it, most writers are aware that taking photos of trains in service might land them in trouble with station staff or, worse, undercover graf squad. Perhaps there’s even a deeper worry that publishing photos could possibly get us into trouble with the authorities, especially online. But that’s more to do with the photos being traced back to us. With my case, the main thrust of the case against me was my intention. That is, what was I thinking and feeling when I decided to publish the magazine? What was my motivation? What impact, if any, did I want the magazine(s) to have?

To the police, the notion was that I intended to “pass on the baton” of graffiti to the new generation – that I wanted the magazine and blog to inspire writers to go out there and paint. In their case, they were trying to prove my “state of mind” at the time of making the magazine. Essentially, they were trying to prove a thought crime – proper 1984 business. A big part of this was the fact that I was an active writer at the time, which, to them, meant the magazine was not “journalistic documentation of culture” but the action of someone who wanted to perpetuate the culture.

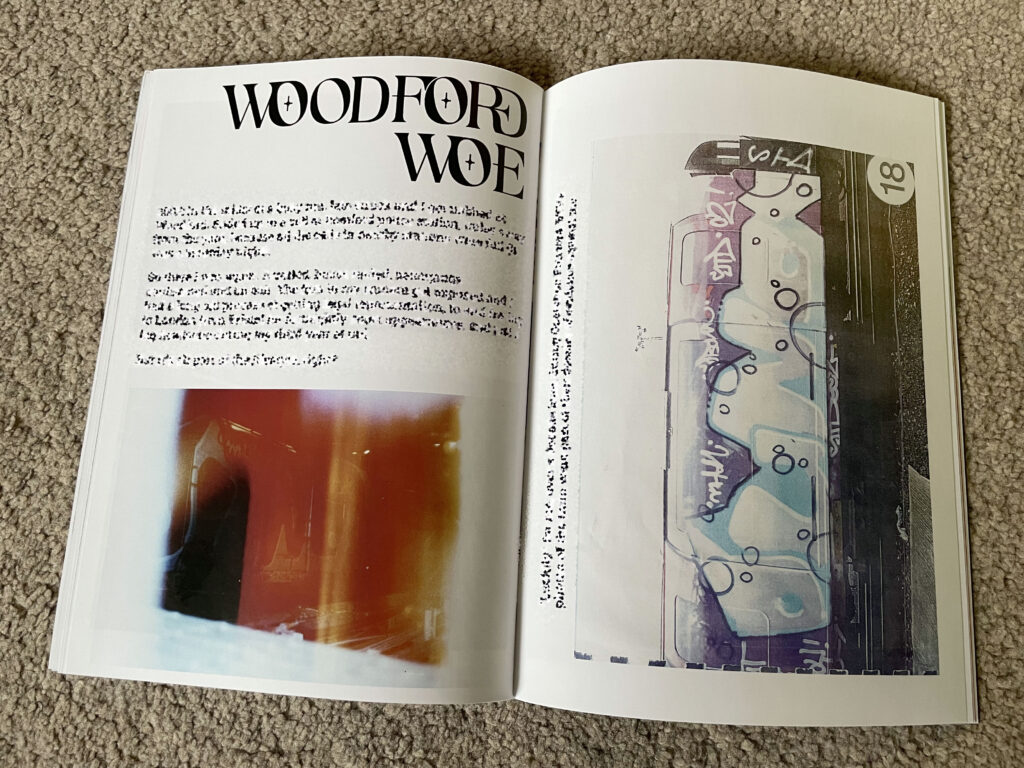

If we rewind to the late 2000s, the UK was going through a torrid time with graffiti. From that period to the early 2010s it was an intense time. A lot of arrests, a lot of people being sent to jail, a few deaths… Train activity, especially tubes, became very high-risk.

We’re used to this in the UK. Our laws and lawmakers have always been tough on graffiti. London’s tube had a hardcore reputation for years due to the high security and seemingly impossible odds of painting its many lines. But this period was particularly gnarly, which is partly why the magazine even exists. After a few people I knew got long jail sentences and others died, I felt like there was a dark cloud over our community. My idea was to do something to raise people’s spirits – not just writers, but their loved ones, too. To show them that graffiti is still very much alive and to, hopefully, bring some positive energy into their lives. That’s why the magazine ended up being called Keep The Faith.

But, in the context of this draconian period, it probably wasn’t a good idea to gather up hundreds of train photos and put them into the public domain. The graffiti squad had a very antagonistic and determined chief, who not only wanted to eradicate graffiti but also seemed to be adept at securing hefty punishments for the writers. He positioned himself as a “graffiti expert”, testifying in court against writers using a dossier he’d created. It was this man who, heading towards the closure of his graffiti squad, targeted Keep The Faith and set about using a charge that had never ever been used against a publisher and their publication before.

I think he probably wanted to score one last big victory before the graffiti squad was disbanded. What we call a “swan song”. Getting me prosecuted would have been a historic win for him and his team. I hadn’t quite grasped this at the time and it’s only been in more recent times when I’ve been able to reflect on the sheer gravity of the whole thing.

Thankfully, after over two weeks in front of a jury at the crown court (and over three years on bail), I was found Not Guilty. History was made in that instance. If I’d have been found guilty, the repercussions were deadly serious. On a personal level, I was facing up to seven years in jail. On a societal level, anyone publishing photos of illegal graffiti could have been arrested and charged. It might have even inspired other lawmakers in other countries to create similar charges. My case set a precedent. In other words, anyone who might end up in a similar situation to the one I was in, can refer to my case in the future.

Back In The Zine Game

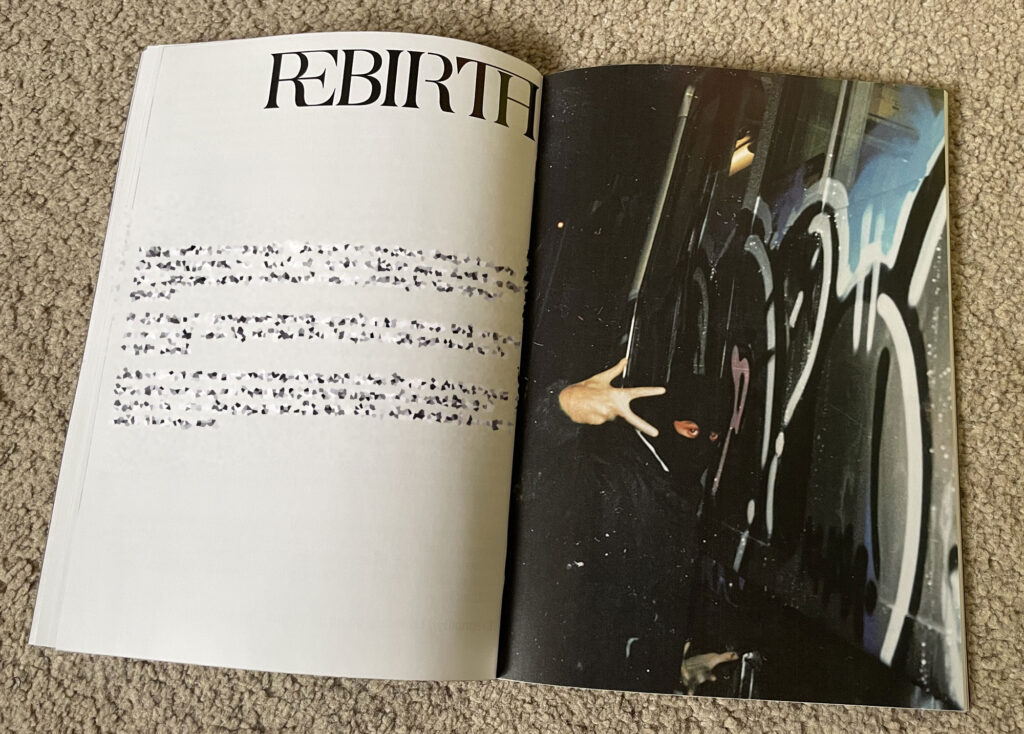

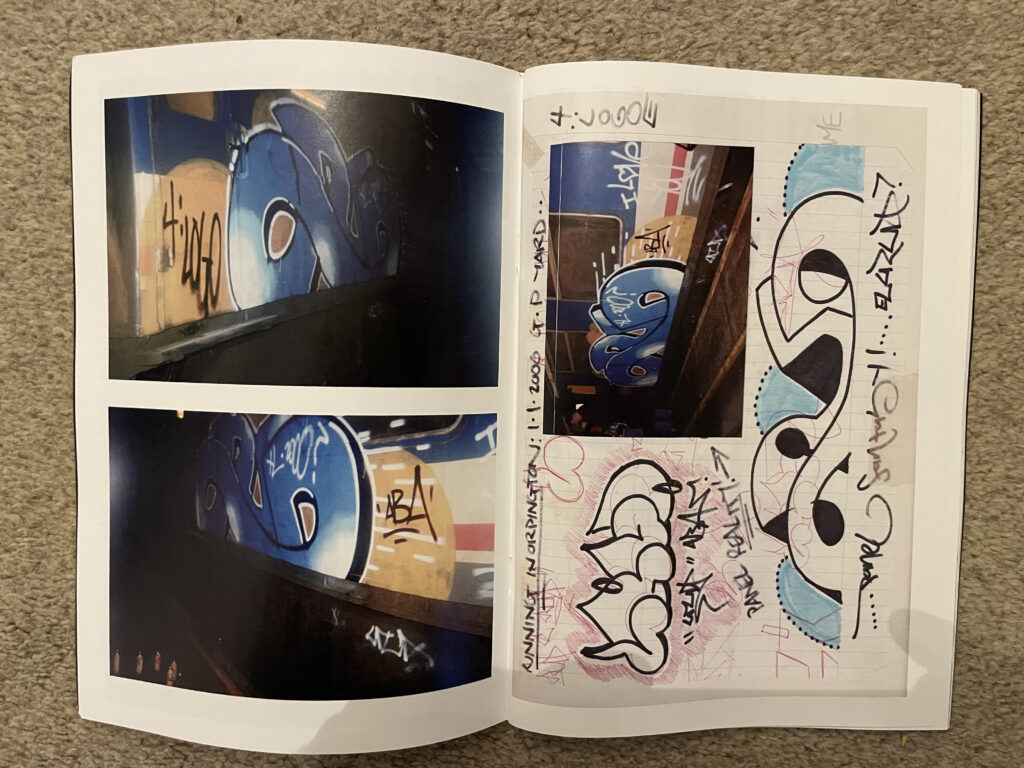

Recently, I published my first graffiti zine since that landmark court case. It’s been over 10 years since I was found Not Guilty. Last February was the anniversary, around that time I decided it was time to share some of my story. So Pandora’s Box was conceived – a 72-page zine that depicts some of my early history. I wanted to tell my story, to take people into my teenage world, and to contextualise my roots so people can understand how I ended up being embroiled in a historic court case.

The zine takes you back to the 90s and early 2000s. A very formative period of my life, when graffiti and music were pretty much all I cared about. At first it was all about traveling around the city, from the age of 13, taking photos and sketching at home. By the age of 18, I was knee deep in the lifestyle. All the clichés; permanent ink-stains on my skin, nocturnal sleep patterns, a persistent desire to write my name on things and see it running, reconnaissance missions, a room full of paint… you know how it goes. I loved it. A snapshot of those times is captured in the zine.

Reflecting On 10 Years Since The Case

If I could go back, I don’t know if I would change anything about the court case experience. It was very tough but it sparked some deep shifts in me and how I live my life. I’ve spoken to so many people about it in the years since and the majority of them always say, “It had to be you”. I don’t mean this in a big-headed way but it makes sense. The responsibility had to fall on me. Not because I’m special, but it’s just how it was supposed to be.

I don’t know if anything like this has ever happened anywhere else in the world. It wouldn’t surprise me, but I’ve never heard about any. Today, we see the proliferation of graffiti all over the digital realm. Social media is overrun with images of trains, people painting live in the yards, GoPro footage everywhere… branded crew pages, and some of the biggest writers in the world with their own Instagram and TikTok pages. It’s strange to me – although I have my own page – that, only 10 years ago, this whole thing could have been made illegal. But also how, back in those days, it was not the norm for people to publicise themselves on social media to the extent they do now. Not so much a criticism, just an observation and something to think about.

What will I do next? I’ve been asking myself. Well, I have so many photos from back in the day, I would like to put more zines out there and maybe even do a proper book project at some point. I’ve worked as a journalist for over 20 years, and my core skills revolve around research and storytelling, so I thrive when I’m involved in projects that utilise those skills. Watch this space, more to come….

Pandora’s Box – Limited Edition Bumper Zine

Format: A5 (148 mm x 210 mm)

Orientation: Portrait

Binding: Staple (saddle-stitched)

Pages: 72

Printing: Full Colour (CMYK)

Paper Stock: 130gsm Silk (interior pages)

Cover: 170gsm Silk

Finish: Smooth, semi-gloss finish

Country of Printing: UK

Shop: ktfldn.bigcartel.com